The Cockatiel Handbook, 40 years later

I have an article on my personal blog about my experiences keeping birds: My Life With Parrots.

When I first decided to breed cockatiels at age 12, there was only one book on the subject that I could find: The Cockatiel Handbook by Dr Gerald R. Allen and Connie Allen. Not to be confused with two other books with the same or similar names. Over the years, two different cover images were used, but the text is the same.

Dr Allen is a very interesting character. He’s considered one of Australia’s foremost fish biologists, authoring 33 books and over 400 scientific papers. All about fish. And then there’s The Cockatiel Handbook, which is never mentioned when you read about him.

Moving to Australia with his family in 1972 after finishing his doctoral thesis, he fell in love with the native parrots of Australia, eventually building aviaries and breeding them. He failed to find any good books on cockatiels at the time, so he wrote one. As someone who exclusively keeps Australian birds and has always loved them, I wonder whether my inspiration came from this book.

Overview

This Cockatiel Handbook was my first bird reference of any kind. I’ve carried it with me for 40 years and only recently read it for the first time in decades.

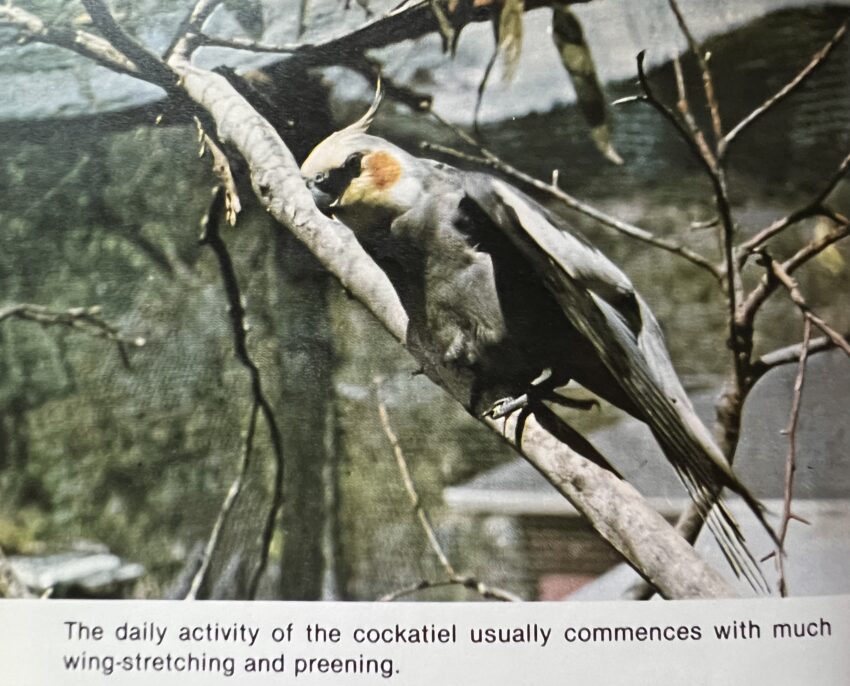

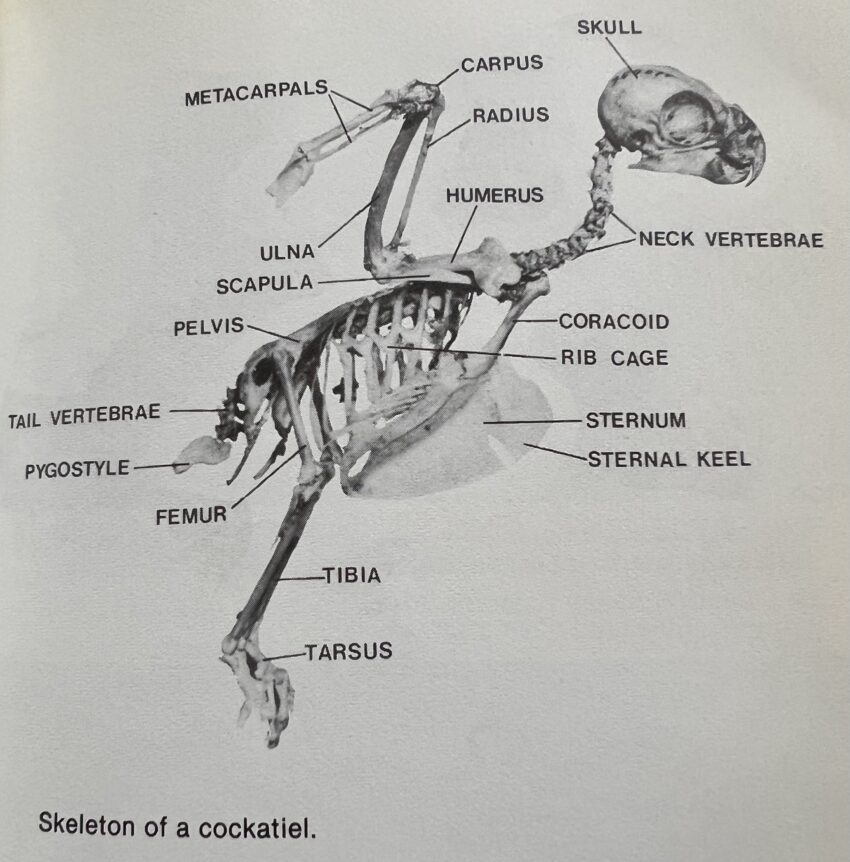

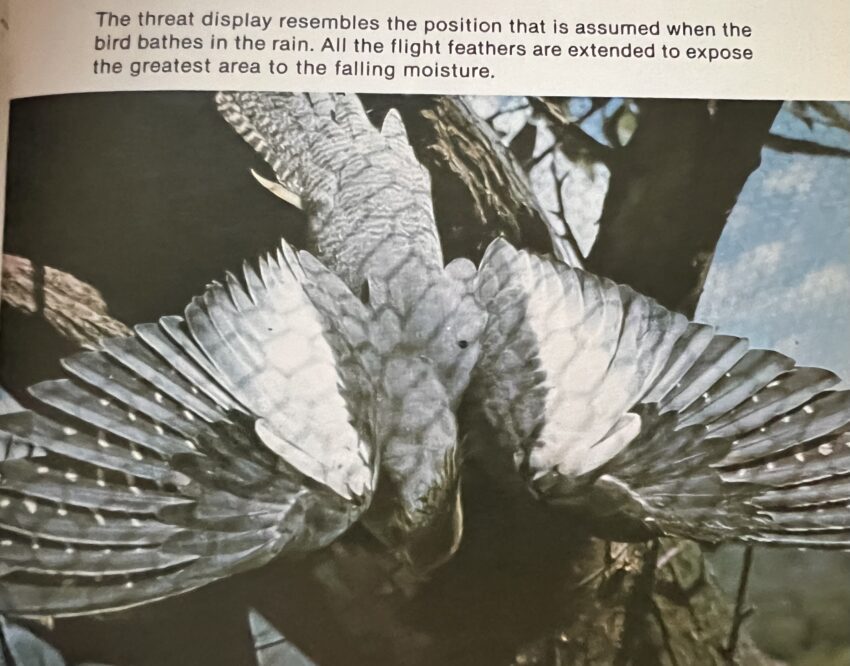

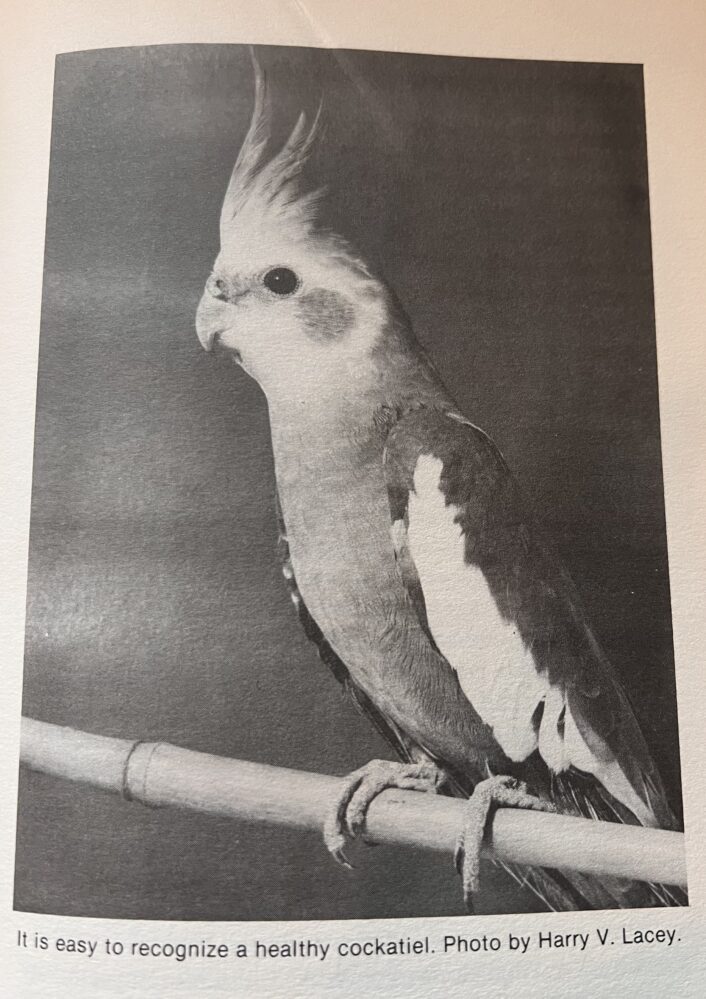

I am struck by how unique it is compared to other bird-keeping books I’ve since read and how well it holds up today. Since the author is a scientist, he spends much more time on evolutionary history, anatomy, and taxonomy—and there are extensive details on how cockatiels eat, breed, and behave in the wild. This background is leveraged to present useful information to cockatiel keepers and breeders. It’s full of great photos and illustrations—over 200 in colour and black-and-white. Quite a lot for a book with about the same number of pages.

I’ve always appreciated that his book isn’t alarmist like many bird-keeping guides, scaring you into thinking that everything will kill your bird. He opens the book by saying:

We emphasize that the methodology described herein should not be considered the only formula for achieving successful maintenance and breeding. For example, there are a myriad of good aviary designs, and professional aviculturalists have different opinions about diets and the rearing and taming of young birds. We acknowledge that there are many different and equally successful approaches to the art of cockatiel keeping. Also like humans and other animals, cockatiels tend to be individualistic with regard to behavior, and the patterns described in this book are based mainly on the animals in our personal collection supplemented with observation of wild cockatiels from central and northern Western Australia.

This made me feel like experimentation was a reasonable thing to do. A rigid set of rules can sometimes fail you when encountering a new situation. You need confidence and common sense to learn new things or improve on the past. The book is also fairly succinct, so it’s quick to read and not stuffed with too many extraneous details.

I thought I’d review each chapter and comment on some of the content.

Introduction

The connection between birds and dinosaurs was not fully established when this book was written. It was a hot topic of debate. Today, we know that birds are dinosaurs. It’s amazing how things have changed!

Nymphicus hollandicus and the science of taxonomy

I was aware of the “weero” moniker for cockatiels, but this book taught me some new ones: bula-doota, wee-arra, toorir, wamba, and woo-ra-ling. I also learned that the calopsita moniker comes from one of the proposed genus names in the 19th century.

I learned that cockatiels and cockatiel eggs were food for humans at one point in history. Not surprising, but it’s difficult to think about!

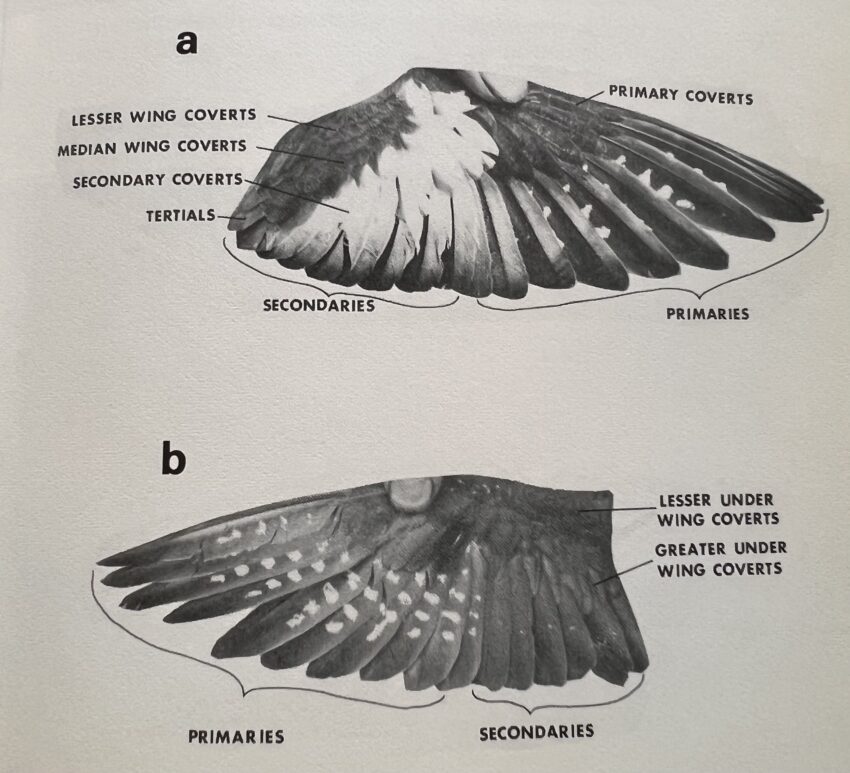

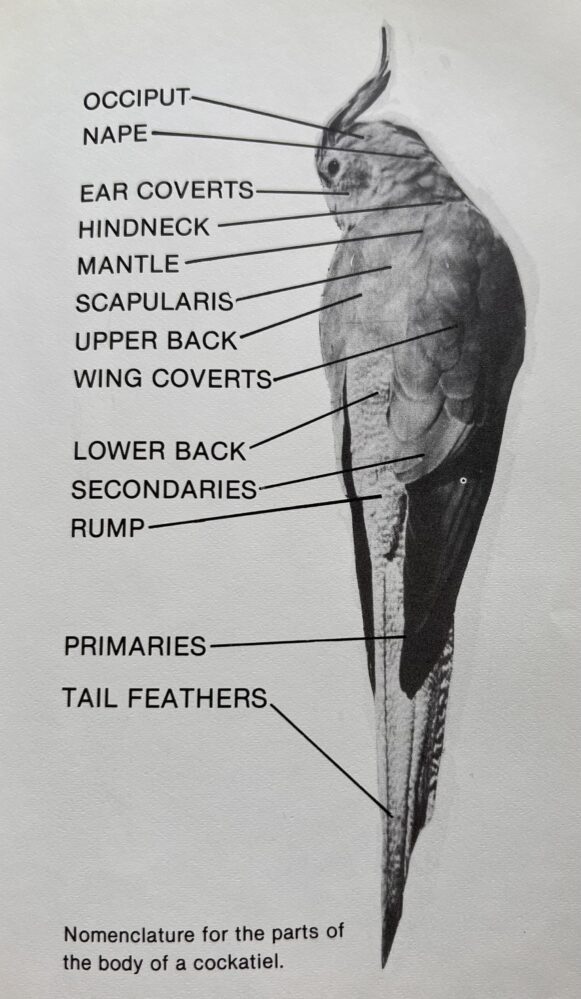

Cockatiel anatomy

This book still has some of the nicest and most complete physical diagrams of cockatiels I’ve run across. Here are just a few of them.

It was great to see the author discuss his experience mixing multiple bird species. I’ve written an article on this topic. He also successfully housed many of the same birds I have: cockatiels, budgies, red-rumped parrots, Bourke’s parrots, and grass parrots (neophema).

Natural history of cockatiels

This is one of the only reference books mentioning the cockatiel’s wild diet in detail.

Cockatiels feed on the seeds of grasses, herbaceous plants, shrubs and trees, and on grain, fruits, and berries. They are fond of acacia seeds [and] fallen wheat grains. They also attack standing crops […] large flocks visit the paddocks to feed on ripening sorghum, millet, and pannicum. They have been observed feeding on mistletoe berries.

Recent research—which I will write about at some point—shows that cockatiels strongly prefer unripe seeds and will prefer them when ripe seeds are present, even sunflower seeds!

Cockatiels as pets

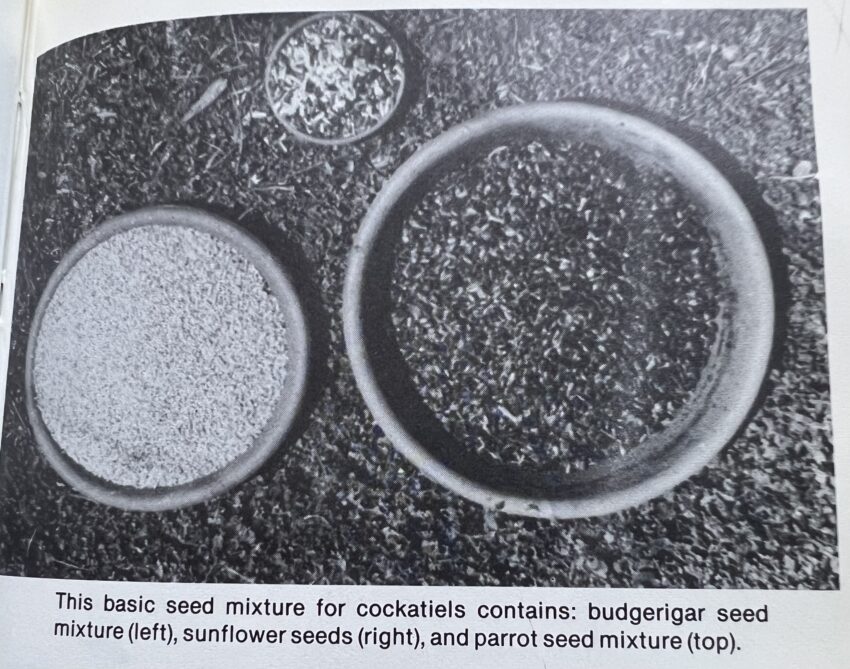

Drawing from observations in the wild, the author recommends a similar diet for captive birds.

Healthy cockatiels seldom present a feeding problem. Most of the basic nutrients can be provided with the commercial budgie or parakeet food, supplemented with daily feeding of fresh green food […] some unsalted sunflower seeds and mixed parrot of cockatoo seeds are excellent supplements.

Although I prefer a more varied seed diet, the author’s recommendation is a good balance of high-carb seeds (budgie mix) with those that are higher fat (sunflower seeds and parrot mix). I’ve written extensively about processed (pelleted) food and how it made people and birds fatter and less healthy. I like to think that the author would feel the same about pelleted diets as I do.

The author mentions providing grasses to cockatiels, which I’ve also written about.

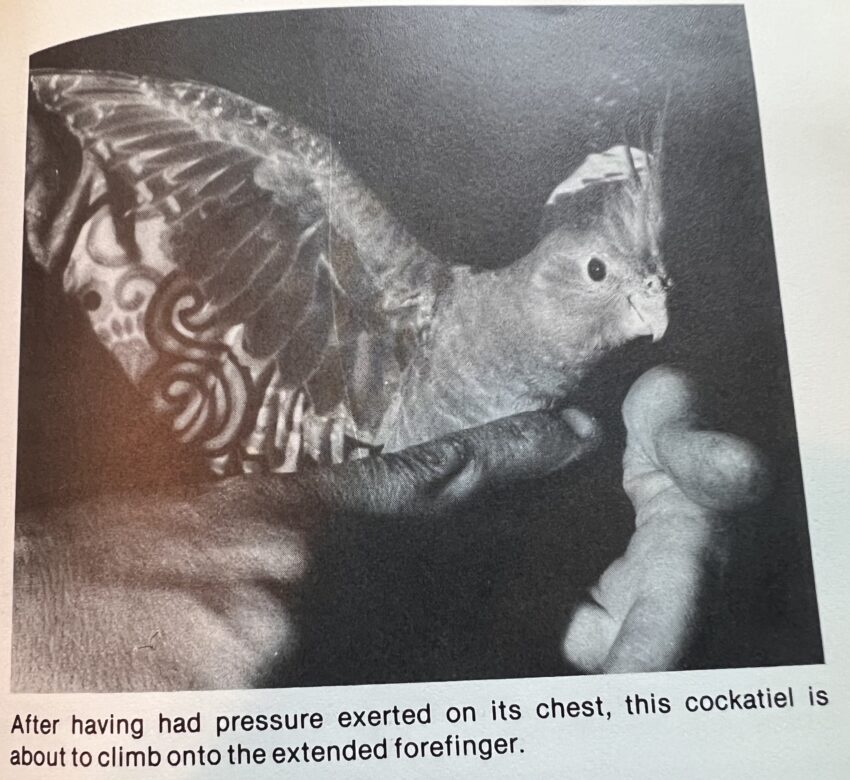

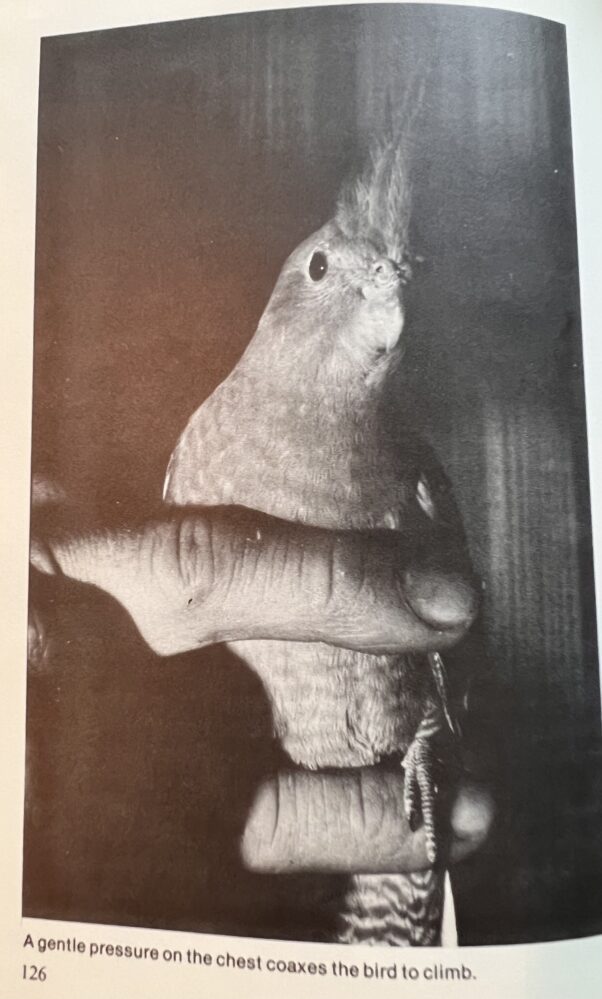

The one area that has changed dramatically since this book was written is how we tame and train birds. The author suggests always doing wing clipping, which essentially forces the bird to get up on your hand as there is no escape. The downsides of clipping are not mentioned at all. Clipping is controversial today, but back then, clipping was very common. Also, the suggestion to clip just one wing was an idea that has thankfully died out.

It was also common back then to nudge your bird off balance as a technique to force them onto your finger or hand during the taming process. This is not consistent with the “force-free” training methods of today, which I think build trust and a better relationship with a bird.

The cockatiel aviary

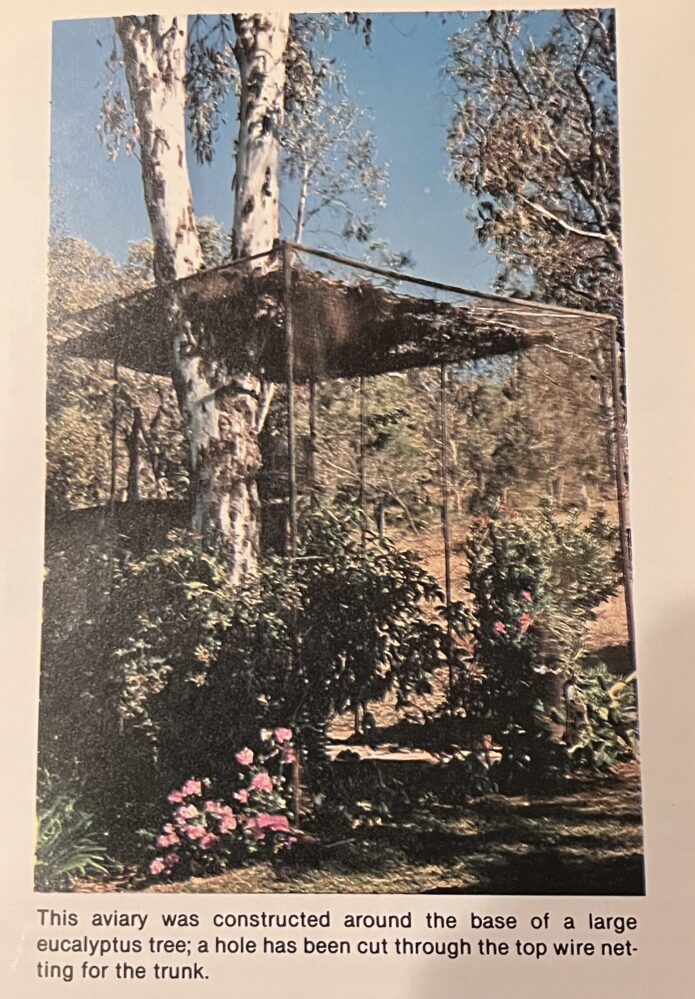

Although I didn’t refer to this book in my aviary design, I appear to have been heavily influenced by it. Dr Allen tried to mimic the natural cockatiel environment in his aviaries by providing a dirt floor for rummaging. He would plant things in the soil and also dump spent seeds on the ground so they would sprout. He incorporated his existing yard into the design.

The author provided his estimates for sizing an aviary, which I’ve not been able to find anywhere else. He recommends 100-200 cubic feet of space per bird. I get asked this question a lot, and his estimates match what I usually recommend.

Breeding cockatiels

When the book was written, the demand for cockatiels outstripped supply, and the gap was bridged by wild-caught birds. Breeding was a useful option to meet the need for pet birds so that importation could stop. This practice ended in the early 1990s. Today, I don’t recommend people raise birds unless they cannot be obtained via a bird rescue or animal shelter.

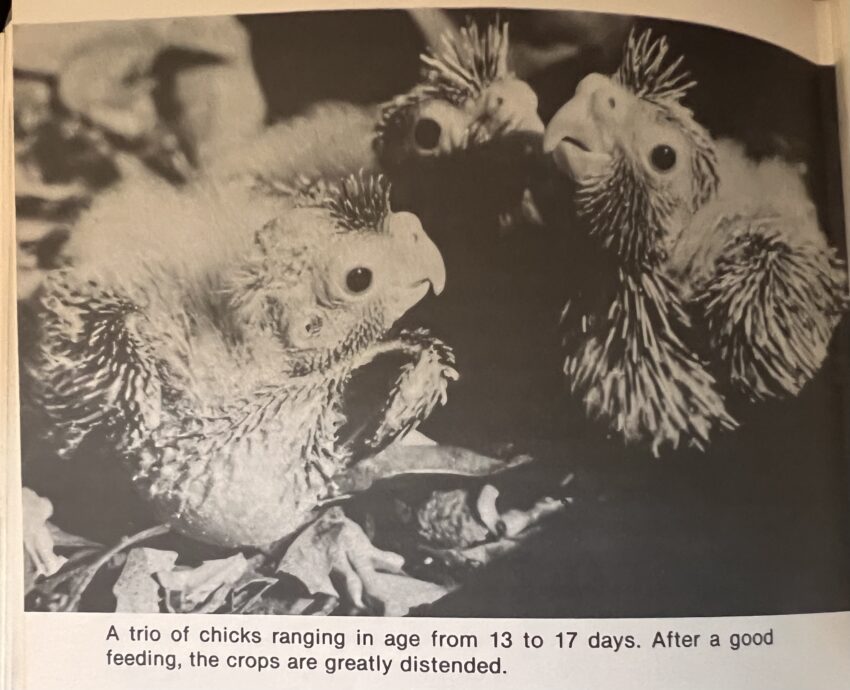

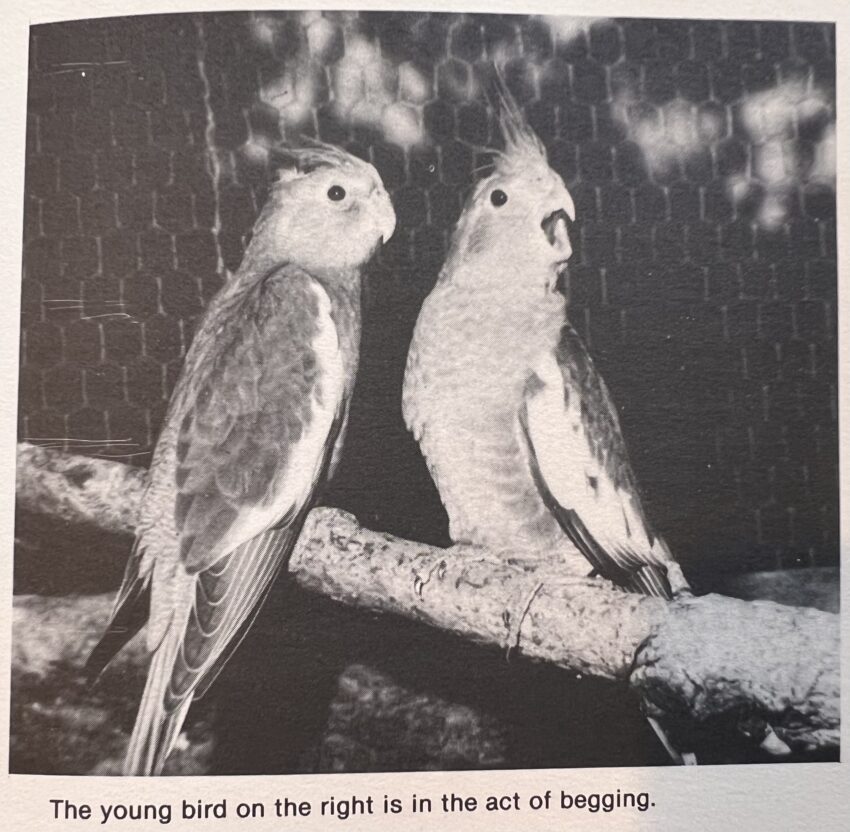

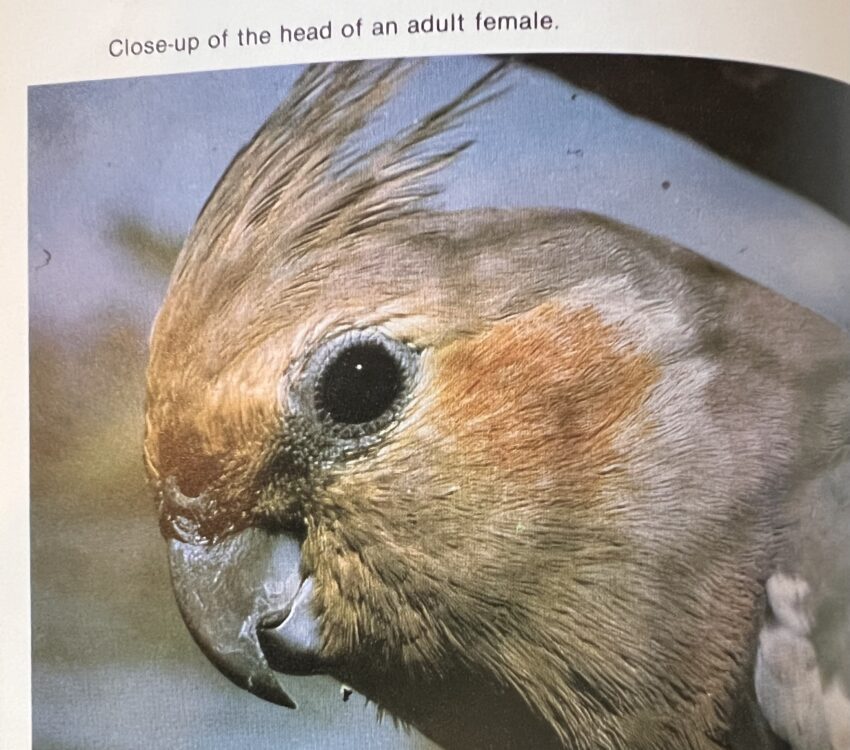

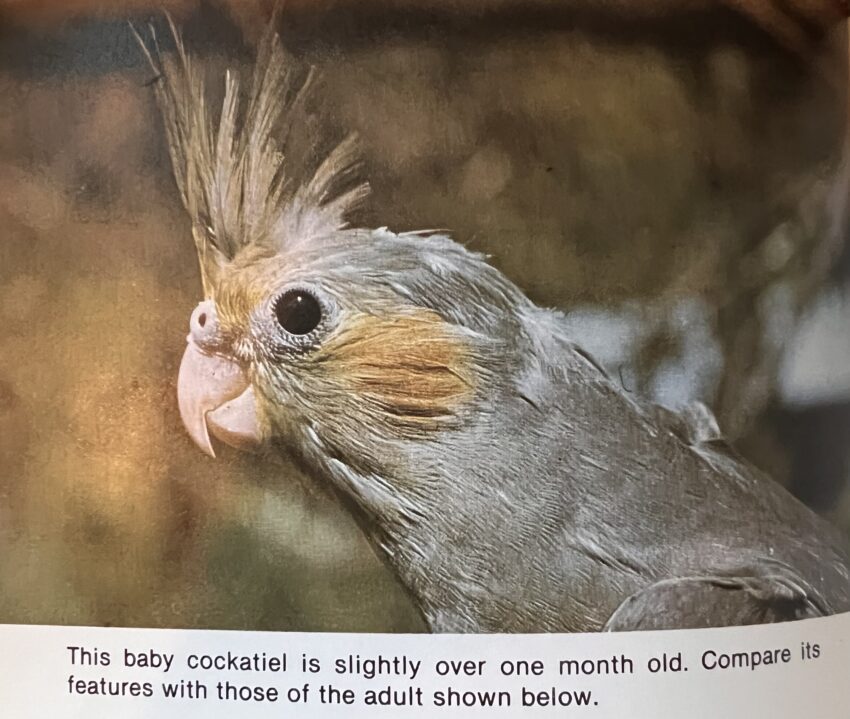

I mentioned the photos before, but the photos of cockatiels at all stages of life are amazing, from recently hatched on into adulthood.

The author is very opinionated about cockatiel mutations!

We believe that captive birds are virtually identical to their wild relatives are far more interesting to keep than “mutated freaks”, which may be colorful but have been domesticated to such a degree that the natural beauty resulting from literally thousands of years of evolution can no longer be appreciated.

In those days, the mutations were relatively rare and consisted mostly of pearl, lutino, and pied.

Diseases and illnesses

I strongly agree with his general advice that sick birds should be placed in a “hospital cage” where they can rest and stay warm using a heating pad or light bulb. Sometimes this is all an ailing bird needs to recover on its own.

He provides good no-nonsense advice for identifying illnesses without being alarmist. Many books immediately recommend taking your bird to a vet, which is very stressful for a bird. Also, it can be a long wait to get into a vet, and there are things you can do to alleviate suffering in the meantime. Or, in serious situations where you can’t get a vet appointment in time, there are home treatment options that might prove useful.

For example, he has advice or home treatment for egg binding, a potentially life-threatening condition.

[Egg binding] occurs when the female is unable to naturally expel an egg which is lodged in the cloaca or lower oviduct. If not dislodged, the egg will prevent the passing of waste products and will result in toxemia and subsequent death. If detected in time, an egg-bound cockatiel can be successfully treated by lubricating the cloaca with several drops of lukewarm vegetable or mineral oil. This will probably require two persons, one to hold the bird in a belly-up position and the other to apply the oil very carefully in the vent with an eyedropper. After treating the bird, place it in a heated hospital cage or in a cardboard box placed on a warm heating pad. The egg will pass within a few hours in most cases. However, if the oil treatment does not dislodge the egg, try coaxing the egg out by applying presure with the fingers. Hold the bird in a belly-up position and locate the upper end of the egg, applying pressure to gradually force it down the oviduct toward the vent.

Not something I’d like to do myself, but in a case of a suffering bird and a long wait to get to a vet, I’m happy to have the option.

The author brings up several times that birds have good blood clotting abilities. This may surprise many people as this is counter to what you’ll read almost everywhere. But the author is correct! A healthy bird has excellent clotting abilities, and there is no need to panic when a bird is bleeding. In the case of severe bleeding, pressure or a clotting powder can help. But the same is true of humans if wounds don’t stop bleeding.

The author always keeps antibiotics on hand, which is interesting advice, especially for those with lots of birds. Although you must be careful not to over-treat birds with antibiotics, if you have a fluffed-up bird that is very ill, it might be worth risking an antibiotic as the bird may die before you make it to a vet.

Conclusion

The author provides a pretty extensive bibliography at the end. I appreciate that the book not only cites references for many of its claims but also provides other resources to tap. It doesn’t present itself as the last word in caring for cockatiels.

One of the most important takeaways from this book is the power of learning how cockatiels live in the wild. This seems obvious, but I’m always surprised by how few people consider it. For example, cockatiels are ground feeders in the wild, yet most people use seed cups attached to a cage or perch. I’ve written an article about learning from your bird in the wild and also one on the wild diet. It seems likely that this book is where I got the idea.

I have a lot of respect for this book and the author. I think he’s written a cockatiel guide that is still relevant today and contains wisdom lost in the modern era, where panic rules over common sense.