Birds and flickering lights

What is flicker?

In its simplest definition, flicker is the constant fluctuation of light output from on to off.

LEDs: Fighting Flicker

In the US, the power that comes in through our outlets cycle at 60 times per second. Instead of one continuous stream of electrons, it goes ON and OFF 60 times per second (referred to as 60 Hz). Many light bulbs also flicker at 60 Hz and cycle towards full brightness and full darkness. We call that the flicker rate.

(I’m going to gloss over this but the circuitry connected to a light source can create light that is a higher flicker rate than 60 Hz. Many fluorescent bulbs are 120+ Hz for example, and some LED lights are even higher than that. This is an extremely technical discussion that you can read more about in the research I’ve referenced in this article).

Many people never notice the flicker, but we probably all know at least one person that can see it in a light bulb or TV or computer monitor.

It’s not all about the flicker rate, though. You can have a 60 Hz bulb that flickers like mad and another one that is a thing of beauty. That’s where we bring in another term called flicker percentage.

What is flicker percentage?

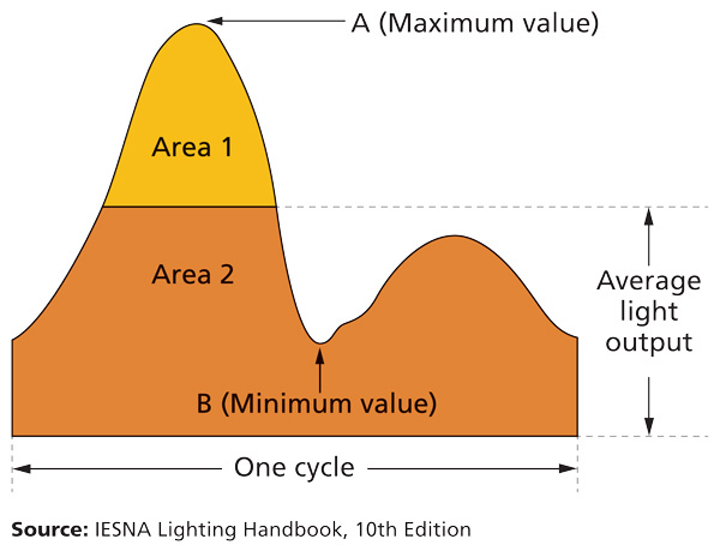

As a light flickers, the light intensity follows a grossly simplified path like this. Each peak in the graph is the brightest point of the bulb and the valley is the dimmest. Each peak is 1/60th of a second apart if this is a 60 Hz bulb.

If we were to look at just one cycle (1/60th of a second), it would look more like this:

Focus on the maximum and minimum values and ignore the rest. Here’s an official definition of flicker percentage:

Percent flicker describes the modulation [i.e. change] in light output using the maximum and minimum intensity values and has a scale from 0 – 100% [with 100% being the most flicker]

FAQ – Flicker in LED Lighting

Here’s where the rubber meets the road. This passage below explains why it’s not all about flicker rate. Flicker percentage is of immense importance to whether we perceive a light as flickering or not.

The majority of modern artificial light sources connected to an [outlet] will fluctuate or flicker, although the frequency and intensity of flicker will vary with the lighting technology. Incandescent bulbs flicker at the frequency of the electrical supply (60 Hz), although the intensity of flicker is low (low flicker [percentage]), whereas fluorescent lighting extinguishes and returns to full brightness twice over each voltage cycle (120 Hz), leading to a pronounced flicker effect (high flicker [percentage]). LED technology is also increasing in popularity particularly for street lighting and these lamps also have a high flicker [percentage].

Potential Biological and Ecological Effects of Flickering Artificial Light—Inger et al—2014 May 2014

Why does this matter?

Flickering lights have been proven to cause a whole host of health problems with both humans and animals.

Major concerns have been raised about the impacts on human health and well-being of living and working under artificial lights, both for typical behavioural patterns in developed countries (e.g. regular periods of evening/night spent under artificial light), and for more acute exposures (e.g. night-shift workers). Documented effects of flicker include headaches, visual effects, and both neurological and physiological symptoms. In some cases these arise under flicker rates that individuals can visually perceive. In others cases however they occur at higher rates which cannot be perceived by the individual but have been demonstrated to produce detectable physiological and neurological effects. In addition, there is some evidence, in a limited number of species, that flickering lamps can have a range of effects on non-human animals and that these effects can be produced by flicker that may or may not be perceivable by the animal.

Potential Biological and Ecological Effects of Flickering Artificial Light—Inger et al—2014 May 2014

The key point here is that you don’t have to even perceive the flicker to have health effects from it. This might be the most important point in this whole article.

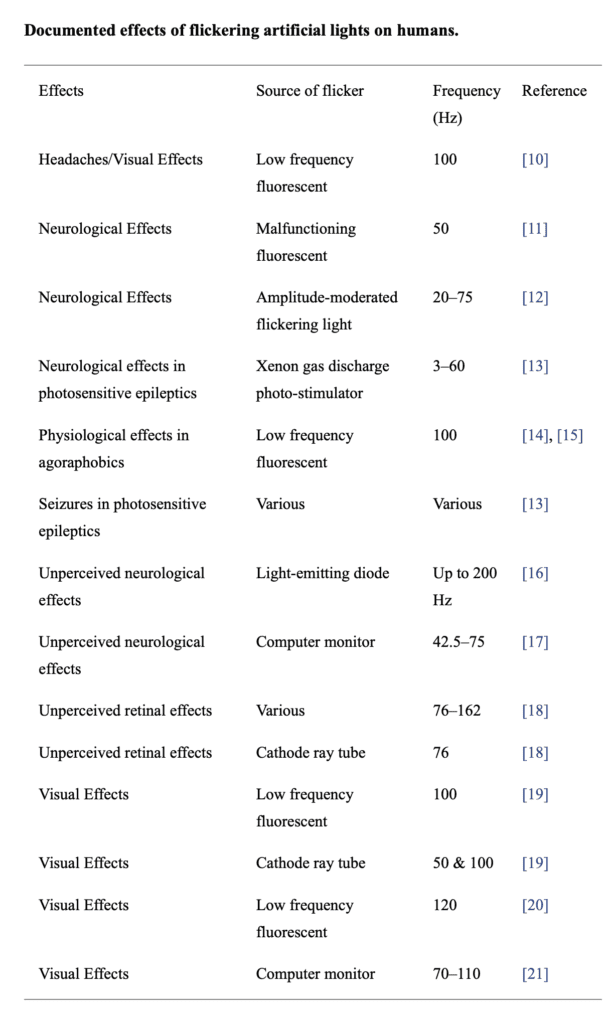

In the interest of information overload, here is a table showing human effects from flickering light sources, many of which we would never use, but it effectively makes the point connecting flicker to health problems.

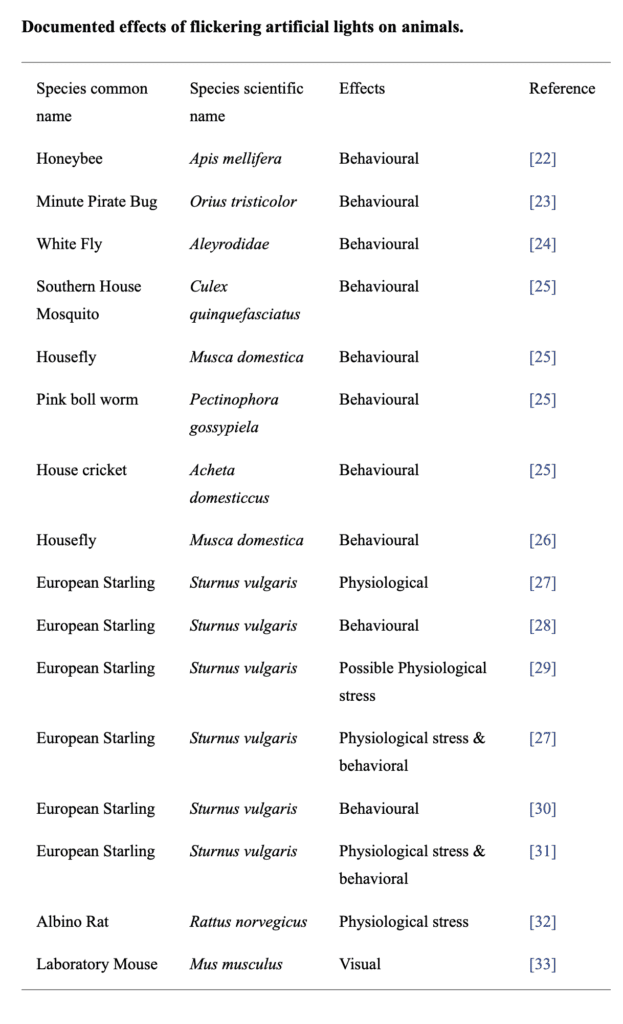

And here is research on the effect on animals. Note that CFF means “critical fusion frequency”, the flicker rate above which an animal no longer perceives it as flicker.

Our results clearly demonstrate how a significant proportion of animals, particularly fast moving diurnal birds and insects have the potential to perceive the flicker of electric lamps, which has been demonstrated to have detrimental effects on both human and non-human species. When we also consider that in the case of humans, flicker can produce symptoms when it cannot be perceived (but can invoke measurable physiological changes) we suggest that, in addition, any species with a CFF of 60 Hz (as in humans) or higher, including many other mammals, and some crustaceans, reptiles and fish, have the potential to be affected by flicker.

Potential Biological and Ecological Effects of Flickering Artificial Light—Inger et al—2014 May 2014

And here is a table showing animal effects of flickering light sources. Even though it doesn’t show flicker rates, it documents that flicker, perceived or otherwise, has real health effects.

Flicker threshold

Every species has what is known as a flicker threshold, which unfortunately is measured in Hertz and doesn’t take into account flicker percentage. However, if we look at the flicker threshold of humans and birds, we can see that birds are 80% percent more sensitive to flicker, given the same light source.

- Human = 60 Hz

- Average bird = 108 Hz

So, if you see the flicker or have health effects from flicker you can’t see, your bird is probably suffering far more than you or possibly in worse ways that we don’t know about. Birds are known for being called “two eyes with wings”

What bulbs should I buy?

So, what type of bulb is the best to use for artificial light? Fluorescent? LED? Well, dammit. There’s no good answer to this question.

Many people assume fluorescents are flickering maniacs, but it turns they’ve improved significantly over the years and some are just as good as the old fashioned incandescents. Many people think LEDs must be amazing at everything since they are new, but they can range from abysmal to better than anything out there.

You won’t find information on flicker on the packaging of any light bulb. At least any that I’ve ever seen. You could try calling the manufacturer and ask for flicker rate and flicker percentage and see how far you get.

One thing you can do is check the package and see if it says that it is Title 24 compliant. This is a California standard that includes provisions for flicker.

Light source in combination with specified control shall provide “reduced flicker operation” when tested at 100 percent and 20 percent of full light output, where reduced flicker operation is defined as having percent amplitude modulation (percent flicker) less than 30 percent at frequencies less than 200 Hz.

Measuring Flicker: California’s JA10 Test Method and Its Uses

This means that at a very high flicker rate of 200 Hz (or lower), the lights must have less than a 30% drop (I’m simplifying) from the maximum and minimum amount of light as it flickers. This means that a light of 200 Hz or higher doesn’t have to meet that requirement but that’s a pretty high flicker rate.

Unfortunately, an excellent website that tested LED bulbs for various criteria has vanished off the planet, but I will update this page if I find a new credible source. There are no practical or inexpensive ways to test for flicker in your own bulbs.

Later I’ll be reviewing some bird cage lights that have a great flicker profile based on some testing with a no longer available application that only runs on very old iPhone hardware. Could it be any harder to find good lighting?

Conclusion

- Buy Title 24 lights

- If you see lights flicker, your birds will see it much worse than you

- Call manufacturer. They need to know people care.

- Don’t assume LEDs are better

- Don’t use artificial lights during the day if you have enough natural light

- Keep reading this blog as lighting is a passion and I plan to keep writing about it.