Tracking technology for birds

Let’s start with cats

If you lose your cat and they end up at an animal shelter, someone will scan them for a microchip. Provided you’ve kept your registration up-to-date, a happy reunion with your pet is in your future. Microchips typically cost less than $50 at the vet and last for the lifetime of the animal.

If they don’t end up at a shelter and you want to find them yourself, there are GPS tags you can attach to a collar and track them on a smartphone. They start at around $50 and go up quite a lot from there. Often, they have a monthly fee (sometimes as much as $15/month). Battery life is typically no more than a week, which means you have to stay on top of it.

Here’s one of the highest-rated ones.

An important point about these GPS trackers is that the cat’s location is periodically broadcast and collected by a server. So, anytime you want to know where you cat is or has been, this information is at your fingertips.

What about birds?

Birds present some very unique challenges when it comes to potential microchipping or attaching a GPS device.

Microchipping

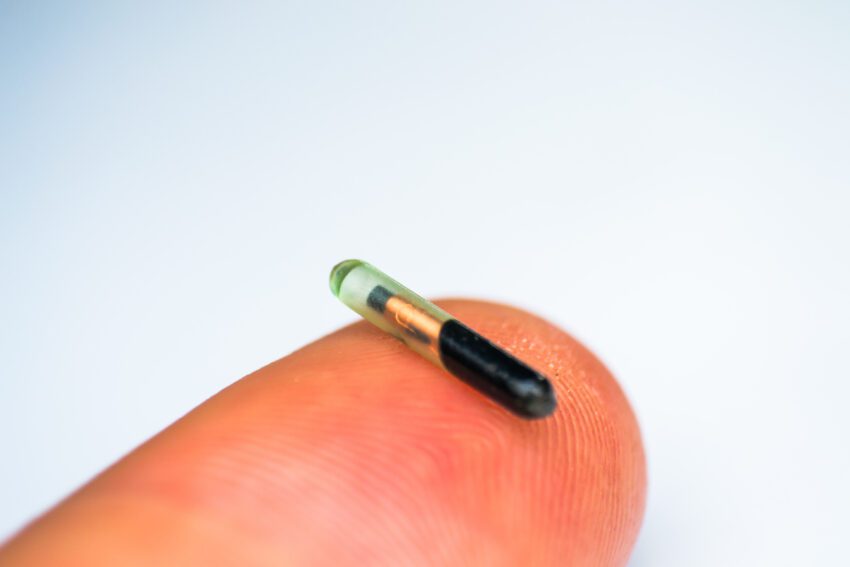

The current generation of microchips generally can’t be used in birds under 100g, which includes most cockatiels and birds smaller than that such as budgies. This is due to the lack of breast tissue to accept the microchip, which is about the size of a grain of rice.

A major issue with microchips in birds is that very, very few birds are currently chipped, so there is a lot of education to be done. Shelters and rescues need to be aware to scan incoming birds just like they do with cats. Even if microchips “take off” for birds, it will likely be many years until the public at large is aware of their existence.

Cost can be closer to $100 to have it implanted by a vet, so it’s not exactly cheap either.

GPS

For years, I’ve done research into this topic and while dramatic progress has been made, it’s likely many more years until something is available for consumers.

Designing something that fits a bird comfortably, doesn’t hinder movement and flight, doesn’t weight them down, and has a battery that doesn’t need to be changed often is a huge challenge!

There are many challenges for GPS “backpacks” for birds:

- The weight of the backpack must be a fraction of the bird’s weight so as not to be a hindrance.

- Fitting is extremely important to avoid irritating the bird, to make sure they don’t fall off, and to allow freedom of movement and flight.

- The backpack needs to be very rugged to withstand the elements and to avoid being destroyed by the bird or their friends.

Not surprisingly, batteries are the critical problem. Continuously recording position based on communicating with a satellite burns out batteries in hours. This is improved by greatly limiting the transmission times to once every few weeks. But this is better suited to tracking migration patterns of birds than locating them at a given time.

The dealbreaker for consumer use is that these GPS backpacks don’t broadcast their positions, they merely store the data in the backpack. Later, the bird must be re-captured and data downloaded to the backpack. Enabling transmission of data to a central server would require substantially more battery power. The much larger cat GPS units need weekly battery refreshes.

As of today, GPS units are being used almost exclusively by wildlife biologists.

However, there is some amazing progress:

- Some backpaces have gotten to be so small and light that they can even be fitted to songbirds!

- Notable species such as the Kea in New Zealand have been using this technology for years now, so there is a wealth of new information being gathered about what works and what doesn’t.

Research

If you’d like to know much, much more, there are two notable studies from the last ten years about using GPS backpacks to learn more about birds in the wild. They can be used to learn about their territories, their mating locations, their diets, and their responses to habitat loss.

Since these papers are very long and involved, I’ll quote a few interesting bits from each paper. First, small songbirds:

Here we tested and deployed a newly developed miniaturized tracking device that weighs ~1 g, combines archival technology with GPS accuracy (~10 m) and can be placed on small songbirds weighing <20 g. Until now, the smallest comparable device available was ~12 g and could only be placed on animals weighing at least 250 g.

Miniaturized GPS Tags Identify Non-breeding Territories of a Small Breeding Migratory Songbird—Scientific Reports—09 June 2015

And large parrots:

Our study is the first reported use of animal-borne GPS telemetry for parrots; as such, it offers crucial insights into the application of this tracking technology for the study of the ecology, behavior, conservation, and management of this large and diverse group of birds.

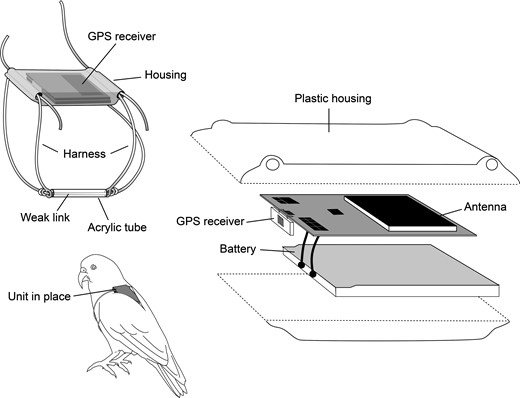

The GPS loggers evaluated in this study comprised a commercially available 20-channel receiver with integrated data storage and passive ceramic aerial, powered by a 380 mAh 3.7 V lithium-polymer rechargeable battery. Loggers were made weather- and bite-proof by removing the receivers from their original plastic housing and sealing them in two layers of ~0.9 mm polyolefin heat-shrink wrap. Plastic tubes (6 mm and 4 mm external and internal diameters, respectively) for attachment of harnesses were fixed to the loggers with superglue before a third layer of shrink wrap was added and sealed. Completed devices weighed ~19 g and were ~60 mm × 27 mm × 12 mm.

GPS telemetry for parrots: A case study with the Kea (Nestor notabilis)—The Auk—18 February 2015

As you can see, these are basically hand-made and assembled products with some improvisation. Not quite ready for primetime!

Conclusion

Microchipping is something worth considering for your parrots, although its low adoption rate currently means it only slightly increases your chances of finding your lost bird. If money is tight, it can be a difficult decision to weigh it against other expenses. As a keeper of small birds, I don’t have any of them microchipped, but am keeping an eye on things.